Strong women did a lot of the heavy lifting in ancient farming societies

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/11/strong-women-did-lot-heavy-lifting-ancient-agrarian-societies

Strong women did a lot of the heavy lifting in ancient farming societies

By Michael PriceNov. 29, 2017 , 2:00 PM

Forget about emotional labor. Women living 7000 years ago had to deal with another lopsided workload: farming. Prehistoric women shouldered a major share of the hoeing, digging, and hauling in early agricultural societies, according to a new study. Now, by analyzing the bones of these women, scientists have shown that their upper body strength surpassed even today’s elite female athletes. The findings refute popularly held notions that early agrarian women shunned manual labor in favor of domestic work, and they suggest that then—as now—a woman’s work was never done.

“People haven’t typically focused on females in this society, [but] it’s very important for understanding … the divisions of labor that exist today,” says Hila May, an anthropologist at Tel Aviv University in Israel who studies evolutionary anatomy, but was not involved in the new work. “I wish we could go back and ask people how they lived, but all we have is bone.”

Bones stretch and twist throughout the lifetime in response to repeated stresses like lifting, pulling, and running. When humans switched from a roving hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a more sedentary, farming-focused existence some 10,000 years ago, their bones followed suit: The rigid, bent shinbones of men found in central Europe between 5300 B.C.E. and 100 C.E.—shaped by muscles constantly on the run—became progressively straighter and less rigid as people farmed more and roved less. But women’s shinbones didn’t change much during this same period.

SIGN UP FOR OUR DAILY NEWSLETTER

Get more great content like this delivered right to you!

Email Address

Sign Up

By signing up, you agree to share your email address with the publication. Information provided here is subject to Science's privacy policy.

Some have put that down to prehistoric women’s focus on domestic tasks that required comparatively less strength. But Alison Macintosh, an anthropologist at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, thought there might be more to the story. “We felt it was likely a huge oversimplification to say [prehistoric women] were simply not doing that much, or not doing as much as the men, or were largely sedentary,” she says.

To find out what was really going on, she and colleagues used a 3D laser imaging system to record models of 89 shinbones and 78 upper arm bones from women who lived during the Neolithic (5300 B.C.E.–4600 B.C.E.), Bronze Age (3200 B.C.E.–1450 B.C.E.), Iron Age (850 B.C.E.–100 C.E.), and Medieval (800 C.E.–850 C.E.) periods in Central Europe. Then they recruited dozens of female Cambridge students—accomplished runners, soccer players, and rowers as well as moderately active nonathletes—and x-rayed their leg and arm bones using a computerized tomography scanner.

Analyzing the bones’ shapes, they looked at the bends and twists that indicated how much muscle was packed on, then compared them with those of their agrarian foremothers. Macintosh found—similar to previous research—that throughout the ages, women’s leg strength has remained largely the same. But when the researchers looked at the upper arm bones, a new pattern emerged: Prehistoric women in the Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron ages would have had about 5%–10% more arm strength than the modern female athletes in the study, the researchers report today in Science Advances.

In fact, the prehistoric women’s bodies most closely resembled those of modern rowers, who specialize in repetitive, unidirectional pulling strength. That’s the same kind of strength needed for digging ditches, heaving around crop baskets and equipment, and grinding cereal grains. Among the prehistoric women, there was also more variation in strength than in modern women. That means that in these early agricultural societies, women likely specialized in various kinds of heavy manual labor, says Macintosh, whereas men split their time between farming and more lower body–intensive tasks like running and hunting.The findings are convincing, says May, and may help explain why bone diseases such as osteoporosis are so common in women today. Evolution may have shaped women’s bone structure to deal with the stresses of life on the move during hunter-gatherer times, and the rapid shift to a more stationary, farming-focused life might have led to weaker bones.

In future studies, though, she would like researchers to look at the nutritional changes that happened after the agricultural revolution. Eating less meat and more grains and vegetables might have also helped shift bone and muscle strength, she notes. Another unanswered question, says Macintosh: precisely how ancient men and women split up the chores.

Posted in: ArchaeologySociology

doi:10.1126/science.aar6222

7 JANUARY, 2015 - 11:29 DHWTY

The mysterious civilization of the Olmecs

Mexico is perhaps most well-known, archaeologically speaking, as the home of the Aztec civilization. Yet, before the arrival of the Aztecs, another sophisticated civilization, the Olmecs, ruled the region for almost 1000 years. Although pre-Olmec cultures had already existed in the region, the Olmecs have been called the cultura madre , meaning the ‘mother culture’, of Central America. In other words, many of the distinctive features of later Central American civilizations can be traced to the Olmecs. So, who were the Olmecs, and what was their culture like?

The Olmec civilization flourished roughly between 1200 BC and 400 BC, an era commonly known as Central America’s Formative Period. Sites containing traces of the Olmec civilization are found mainly on the southern coast of the Gulf of Mexico, specifically in the states of Veracruz and Tabasco. Although the Olmecs did have a system of writing, only few of their inscriptions are available to archaeologists at present. Moreover, there is not enough continuous Olmec script for archaeologist to decipher the language. As a result, much of what we know about the Olmec civilization is dependent on the archaeological evidence.

The Olmec/Zapotec center, Monte Albán, near the city of Oaxaca, Mexico. Source: BigStockPhoto

For a start, the Olmecs left behind much of their artwork. The most famous of these are arguably the so-called ‘colossal heads’. These representations of human heads are carved from basalt boulders, and at present, at least seventeen of such objects have been found. The colossal heads measure between one and three metres in height, and seem to represent a common subject, i.e. mature men with fleshy cheeks, flat noses, and slightly crossed eyes. Incidentally, such physical features are still common amongst the people of Veracruz and Tabasco, indicating the colossal heads may be representations of the Olmecs themselves. Given the amount of resources needed to produce such objects, it may be speculated that these heads depict the Olmec elites or rulers, and were used as a symbol of power, perhaps like the colossal heads of Jayavarman VII at Angkor Thom in Cambodia.

Colossal stone head of the Olmecs. Source: BigStockPhoto

In addition, the Olmecs also produced miniature versions of these giant heads. One such object is a ‘stone mask’ in the British Museum. In contrast to the colossal heads, this mask, which is made of serpentine, is only 13 cm high. This mask has similar facial features to the colossal heads.

Although such features can be seen in the descendants of the Olmecs, some scholars have speculated that the mask represented an African, Chinese or even a Mediterranean face. The mask also has four holes on its front, speculated to represent the four cardinal points of the compass. As the Olmec ruler was believed to be the most important axis in the world centre, it has been suggested that the mask represented an Olmec ruler. Furthermore, there are numerous circular holes on the face, indicating that face piercings and plugs were used by the Olmecs. Due to the lack of Olmec skeletons (they have been dissolved by the acidic soil of the rainforest), this mask may be the closest we can get to seeing what the Olmecs looked like.

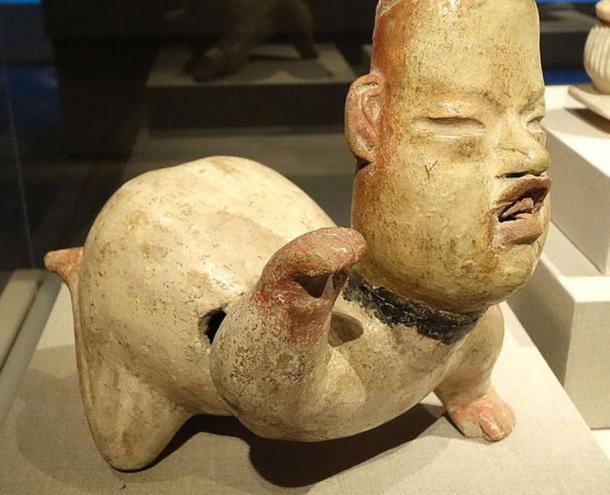

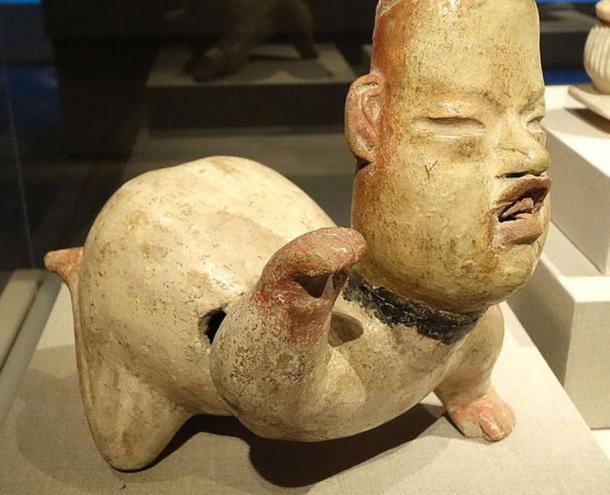

Olmec c rawling baby sculpture (1200-900 BC), Las Bocas, Mexico. ( Wikimedia Commons )

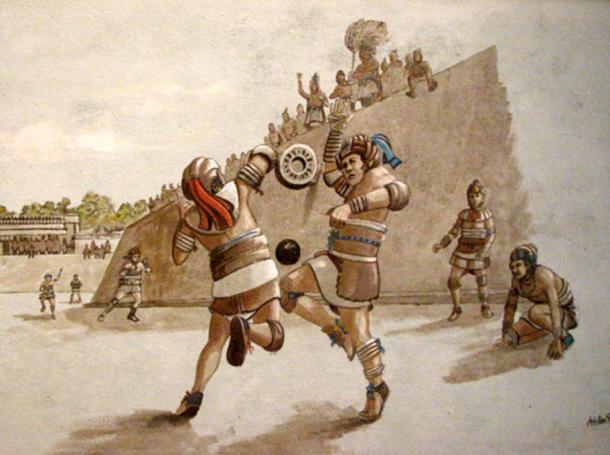

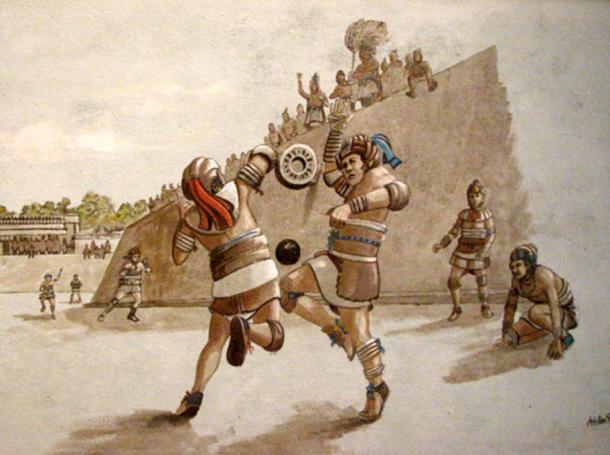

By 400 B.C., the Olmecs mysteriously vanished, the cause of which is still unknown. Although the Olmecs were only rediscovered by archaeologists relatively recently, i.e. after the Second World War, they were by no means a forgotten civilization. After all, the word Olmec itself (meaning ‘rubber people’) can be found in the Aztec language. It seems that the ‘Mesoamerican ballgame’, which was observed by the Spanish when they encountered the Aztecs, was invented by the Olmecs. As this game involved the use of a rubber ball, this may be the reason why the Olmecs were named as such by the Aztecs. This ballgame and several other features of Olmec civilization may be found in subsequent Central American civilizations. Thus, the Olmecs had a considerable amount of influence on these later cultures. As so little is known about the Olmecs today, it would require much more work and research to gain a greater understanding and appreciation of their importance to succeeding Central American societies.

Artist’s depiction of a Mesoamerican ball game ( Image source )

Featured image: An Olmec style face adorns the side of the Mask Temple at the Mayan site of Lamanai in Belize. Source: BigStockPhoto

References

Cartwright, M., 2013. Olmec Civilization. [Online]

Available at: http://www.ancient.eu/Olmec_Civilization/

Available at: http://www.ancient.eu/Olmec_Civilization/